Artistic Anarchy with Hannes Dünnebier

Artistic Anarchy with Hannes Dünnebier

Rebel Threads

*Hannes Dünnebier's Artistic Anarchy

interview & written Alban E. Smajli

Hannes Dünnebier is redrawing the lines of reality. In his world, graphite whispers and cotton screams, creating a narrative that's less about creating and more about upending.

His journey? A plunge from the realms of large-scale drawings into the tactile embrace of textile. This isn't just a shift in medium; it's a manifesto, a defiant stride into the uncharted.

Hannes Dünnebier

Untitled, 2023

hand-stitched & hand-painted heeled boots, acrylic paint & varnish on raw cotton fabric, dimensions variable

.artist talk

Hannes Dünnebier

speaks with

Alban E. Smajli

As he navigates the intricate interplay of pencil and fabric, Dünnebier is stitching a new world order, thread by thread, line by line. With every piece, he questions, he defies, he redefines. His work is a mirror, a window, inviting us to step through and lose ourselves in a universe where the familiar is strange, and the strange, intimately familiar.

Hannes Dünnebier

Untitled, 2023

six pairs of hand-stitched & hand-painted, shoes, acrylic paint & varnish on raw cotton fabric, dimensions variable

Alban E. Smajli //

You've brilliantly used the medium of drawing to explore the challenges of human existence and its relationship with social norms, faith, and superstitions. How do you see the evolution of your artistic journey from large-scale graphite drawings to your recent textile works? And how do these two mediums connect and converse with each other in your practice?

Hannes Dünnebier //

Besides pencil and paper, I was always attracted to raw cotton fabric, that’s commonly used as the base for classic oil and acrylic painting. I looked for ways to incorporate it into my drawing practice, for example by sewing a fictitious drawing garment in which the graphite pencils are lined up in a cartridge belt.

Last year I moved to Antwerp to do a Masters at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, which was a good place to further deepen my exploration of the raw cotton fabric and its interconnection with my drawing practice. One thing that has always particularly inspired me about drawing is that I can create complex works and an entire world with the simplest of means. I wanted to try to do the same with the fabric, which I first manipulated, to achieve different looks and feels and then hand-stitched into clothing and shoe-like objects.

I started by recreating a few pieces from my personal wardrobe, such as a sports jacket or trainers, and then added new, self-invented pieces such as high heels with a hand-painted crocodile skin pattern. I also made a shoulder bag, inspired by a random bag I found in a second-hand shop in Antwerp. For the graduation show I staged everything together in a room as a kind of extended self-portrait.

For me it’s a continuation of my drawing practice and I see the textile works as drawings themselves. The process of hand sewing plays an important role in this. Sewing a piece together stitch by stitch is similar to how I put my drawings together line by line. I guess that in the end my graphite drawings and my textile works all come from the same vague feeling – it just appears in different forms.

Congratulations on being awarded the Lyonel Kunstpreis. The jury mentioned your art offers "an immense interest in the familiar in the seemingly new." How do you interpret this? And how does the cyclical nature of old appearing in new forms manifest in your work?

Thank you! I think when creating an artwork, it’s a lot about the fusion of different existing things, into something new. References can be obvious, and used as a sort of quote, but sometimes it’s nice to keep it subtle and try to create a sense of familiarity that cannot be deciphered immediately. The balance between the known and the unknown, between the readable and the unreadable is something I encounter a lot when making art. It's about trying to carve out vagueness as clearly as possible - if that makes any sense.

The jury also highlighted the role of the human body in your work, both as a site of manipulation and a medium for self-expression. Can you elaborate on how you navigate this dichotomy and what inspired you to approach the body in such a unique manner?

This makes me think of one of my first projects in art school, where I designed furniture for specific body positions, that were all based on having really bad posture. My idea was to use the posture as a metaphor for the mental state of a person and manifest that in an entire interior setting. I always found it weird to have a body, that physically exists in space, and I am trying to make sense out of it by using its presence and its absence as means for my art. The first approach with the furniture has evolved with time but the core idea is still inherent in my work today.

In my graduation show at the Royal Academy, for example, all pieces originally scaled to a body (my body) were shown abandoned and inanimate, evoking a feeling of absence and emptiness. They were still tracing bodily presence and interaction, but also raised questions about their potential autonomous existence.

Hannes Dünnebier

Sorry not Sorry, 2023

hand-stitched and hand-painted shoulder bag, acrylic paint and varnish on raw cotton fabric, dimensions variable

In the "Intrawelten" exhibition, you showcased various intriguing pieces from your diploma exhibition "BYE!", including the graphite drawing with the Nelly Furtado lyric quote and other items such as the Styrodur shoes. Could you elaborate on the central theme connecting these artworks and your choice of objects, especially the quote from Nelly Furtado?

In my exhibition “BYE!” I combined different types of works, such as drawings, textile works and styrofoam shoes to create a stage-like setting. The central theme of the exhibition was an imaginary performance, for which I chose “All Good Things” by Nelly Furtado as the underlying soundtrack. I reawakened my love for this song, while I went through a phase of listening to 2000s pop songs as a sort of therapeutic time travel at the time of making the exhibition.

It’s a gloomy and melancholic song but at the same time it’s very hooky – which is a duality that I resonate with a lot. For the exhibition I took out the central line “Why do all good things come to an end?” and placed it as the only colour element onto a large-scale graphite drawing. I like to think about it as a timeless and universal question. Maybe one of the central questions of human existence. It’s a bit deep but not that deep after all.

With your recognition and the support from institutions, what future projects or explorations are you most excited about? And how do you envision the next phase of your artistic journey?

It’s a very busy time ahead, which I am looking forward to. Together with Colombian artist Eduardo José Rubio Parra, I will co-create the second issue of the experimental publication project THE CHOPPED OFF HEAD MAGAZINE featuring new textile works of mine, and I plan on hosting a series of events in my studio here in Antwerp. I also started a new series of drawings, and besides began to collaborate with young fashion designers on my further exploration of textile and garment, which turns out to be a very fruitful conversation.

(c) Hannes Dünnebier - all images seen by Marvis Chan

Unveiling Shadows: Eduardo José Rubio Parra's Artistic Rebellion in a Dual World

Unveiling Shadows: Eduardo José Rubio Parra's Artistic Rebellion in a Dual World

Unveiling Shadows

*Artistic Rebellion in a Dual World

interview & written Alban E. Smajli

Bridging worlds with a defiant stroke, artist Eduardo José Rubio Parra crashes through cultural barriers in his latest interview with LE MILE Magazine.

A maverick of the art world, Rubio Parra, hailing from Colombia and now a creative force in Antwerp, stitches together the raw, untamed spirit of his homeland with the stark, often enigmatic European sensibilities. His art is not a mere blend; it's a provocative dance across continents, challenging the norms of death, afterlife, and the paranormal.

Gone are the days of art confined to conventional beauty. Rubio Parra's work, steeped in the supernatural, dives headfirst into the abyss of the unknown. In a world where cultures clash and meld, he finds harmony in dissonance, creating a visual language that speaks of both Colombia's vibrant lore and Europe's nuanced mystique. This duality isn't just his canvas; it's his battleground, where he wrestles with the ghosts of two worlds, giving them life through his eclectic artistry.

With The Chopped Off Head Magazine, Rubio Parra cuts deeper than aesthetics. It's a visual scream, a raw expression of frustration and a quest for understanding beyond language barriers. Here, images don't just complement text; they lead the narrative, a testament to Rubio Parra's relentless pursuit to articulate the inarticulable.

.artist talk

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

speaks with

Alban E. Smajli

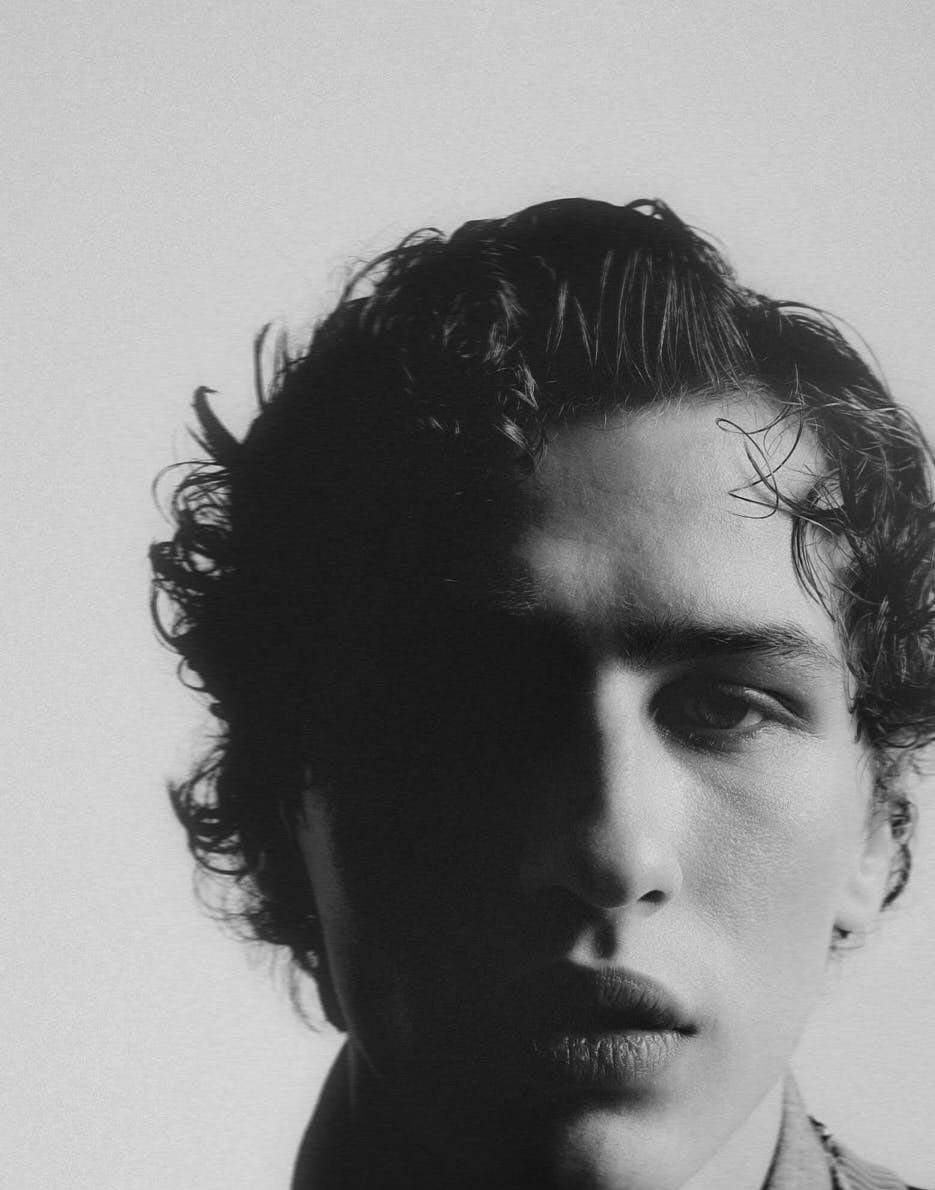

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

ANGEL II, 2023

wearing Martine Rose

Graphite and colored pencils on paper

88,5 x 68 cm

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

ANGEL I, 2023

wearing Loewe

Graphite and colored pencils on paper

88,5 x 68 cm

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

ANGEL III, 2023

wearing Vivienne Westwood

Graphite and colored pencils on paper

88,5 x 68 cm

Alban E. Smajli

Your art intricately ties your Colombian heritage with the European influences you've been surrounded by. How do you navigate this duality, especially when it comes to exploring topics of death, afterlife, and the unknown?

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

It may sound naive, and I probably was, but when moving from Colombia to Germany in 2015, I was not aware of how different cultures really are. It's not only language and customs, but also how we perceive ourselves, our surroundings, and especially that what is unknown to us. Growing up in Colombia, and I would dare say Latin America, stories of the supernatural are pervalent in society. It's not necessary to believe in it to know a person or people who have seen, felt, and or heard something that cannot be explained by the laws of nature.

I've always been fascinated by these stories, and during my time as an art student, I felt the urge to use them as references in the process of making art. But in this process, I soon realized that in Germany the perception of the supernatural is completely different from Colombia and Latin America. This made people not as engaged with my work as I wanted them to be, because it was too far from what they know. So I began to look for a way to "blur" the difference. I wanted my work to serve as a bridge between the world I grew up in -Colombia- and the one I was getting to know -Germany-. I realized that we can all relate to something that is strange or mysterious, especially in a creepy way. So the cornerstone of the bridge turned out to be "uncanniness".

The title of your publication, "The Chopped Off Head Magazine", is evocative and deeply personal. Could you elaborate on the moment or instance when this concept took root? How does the process of "chopping off one's head" to expose internal realities shape the content and presentation of your magazine?

The title of the magazine reflects what I felt every time I talked about my work without being able to make myself understood. Especially in a foreign language. When I had clear images in my head of what I was talking about, but found it difficult to translate them into words. At those times I wished I could cut my head off to show people those images. For this reason, "The Chopped Off Head Magazine" is predominantly visual. The first issue focused on me and my artistic practice, but from the second issue on, I will invite other artists and designers to "chop their heads off". The content and form of the future issues will be significantly influenced by the artists and designers and their interpretation of the concept of the magazine.

You've explored the realm of drawing and its inherent authenticity extensively. How has this exploration evolved over time, and in what ways has it informed your approach to other mediums, such as special effects makeup or performance art?

In fact, it was the other way around. The creation of characters based on me has always been an important aspect of my work. Through these characters, I study, among others, identity, supernatural phenomena, and fashion. Initially, I created characters for photo and video performances, making use of costumes and my skills as a special effects makeup artist.

Lately, I create these characters making use of the medium of Drawing as well. The medium of Drawing creates a distance between me and the characters, allowing them to exist more independently. With a photo and/or video, the characters' existence depends on me disguising myself for the camera. When I see a photo and/or video of these characters, I know I'm seeing myself. With a drawing, I can't assure that. The moment I come to this realization, the characters get to have a life of their own and everything seems possible within a drawing.

With a keen interest in blurring the lines between reality and fiction, how do you see fashion's role in challenging societal norms or perceptions? In what ways does your work in fashion editorials push the envelope in terms of content and presentation?

Fashion has always been a reference in my work. I love watching fashion shows and I'm fascinated by the great variety of characters that are created for a single catwalk. Characters that I only see for a couple of seconds, but their image is so striking that it sticks in my head for a long time. I like to create stories for these characters and imagine who they would be in the real world. I'm especially fascinated by how the same model can embody different characters. This fascination led me to start my latest and probably biggest project. "ANGEL" is an ongoing series of drawings consisting of portraits of different versions of myself. Each version embodies a vision of who I would like to be.

As humans, we have all experienced the desire to be someone else, but letting insecurities or life circumstances hold us back. My drawings allow me to be different versions of myself, unexposed, and be unapologetic about it. Starting from a place of doubt, fear, and limitations, my aim is to create characters and drawings that manifest the opposite and rather "exude" power. For each drawing, my identity is transformed through the use of existing fashion garments and different hairstyles. I see fashion as an enabler for personality change. Despite this work being very personal, identity, vulnerability, and empowerment concern us all.

You mentioned a desire to collaborate with other artists for future editions of "The Chopped Off Head Magazine". What qualities or perspectives are you seeking in these artists, and how do you envision these collaborations amplifying the magazine's ethos and message?

"The Chopped off Head Magazine" is all about collaboration! The magazine is meant to serve as a bridge between different artists, artistic disciplines, and cultures. The idea is to create an ever growing interdisciplinary and intercultural network and an international platform for the presentation of contemporary art, fashion and visual culture. The second issue, called "The Chopped Off Head Magazine: The Dead or Alive Issue", will be co-created by German artist Hannes Dünnebier and will deal with the topics death, life after death, supernatural phenomena, and the unknown. Death, for example, is a topic that concerns us all – however, due to the different contexts in which we grow and develop as individuals, our understanding of this concept is not the same. I am particularly interested in these differences and want to use them as the starting point for creation. The broader the perspectives, the better.

credits

(c) Eduardo José Rubio Parra - all images seen by Marvis Chan

Artist Talk - Interview with Yeule - Scarry Stories

Artist Talk - Interview with Yeule - Scarry Stories

.aesthetic talk

Scarry Stories

* A Glimpse into yeule's Universe

written & interview Hannah Rose Prendergast

In the lifespan of a scar, it takes anywhere from three months to two years for it to soften. It’s not a sore subject for Nat Ćmiel or their alter ego, yeule. Born in heavily surveilled Singapore before moving to London to become a fine arts kid at CSM, the zillennial painter-musician-performer has a lot to say. softscars (2023), yeule’s third studio album, takes the listener on a glitch-pop journey that’s cyber meat for the soul.

We talk over Zoom, where they sit in the passenger seat of their car, “traversing the mist” in LA traffic. It’s a hectic time as they’re preparing to shoot the music video for ghosts. In the backseat, their troupe of stuffed animals is listening intently.

Hannah Rose Prendergast //

When people describe you and your work, an overflow of adjectives comes to mind. As someone who identifies as non-binary, what are your frustrations with the labels attributed to you?

yeule //

As human beings, we need to label things to understand them. In my non-binary experience, it’s not just something worth saying we are. It’s more like I identify as everything; I identify as nothing. I don’t just identify as a woman or a man. I can be in between, or I can be both. It doesn’t bother me when someone uses “she/her” pronouns (instead of “she/they”). I’m very femme-passing most days. The biggest misconception of people who are NB’s (non-binary) is that we find it offensive, but it’s really about other people trying to understand it rather than doing it over and over again. [It’s about] being extremely loving towards these kinds of conversations to do with identity. Like, I see you. I feel you. You’re valid.

There’s a lot of misunderstanding, but people are learning. There’s much more loving energy in your community of people who understand and see you. It’s who you surround yourself by. It’s not always about changing people’s minds. Acceptance is one thing, but it’s also about letting go of the ignorance that prevents you from respecting those who have struggled with gender dysphoria, body image, etc. I didn’t even think gender dysphoria was a thing until I met NB’s — that’s when I found my people. I always felt really safe around them because I felt understood. I think it’s important to protect your space and not be affected by labels created like that.

How would you describe yourself?

In 2021, I had a huge identity crisis. I was becoming a minimalist for a bit. I had to try it out because I’ve always surrounded myself with objects and things I love. Once I stripped all that away, I had an ego death. I could see who I wasn’t and who I was. It was really freaky, and I don’t want to go through it again. I think having an ego is okay; it’s very human. It’s about how you navigate that ego with people. I don’t know how I would describe myself. I’m like a volatile black hole that absorbs things through my lens. I take things I like and hold on to them; their alchemy becomes me.

How is softscars (2023) a natural progression from your last project, Glitch Princess (2022)?

Glitch Princess was all about accepting chaos within digital error. I found out a lot about myself as a perfectionist. It was all about not being able to autotune things, noise clipping, CPO loading. I just exported everything. softscars is similar in bringing it out into the bodily realm. Thinking about scars in a metaphorical way, but also scars on your body, whether it’s from self-harm or surgery. One of my friends recently had top surgery, and they looked so beautiful, showing off their scars.

I call each page in my journal a scar entry. I’ve been doing that for three years. That’s when I became semantically obsessed with the word scars. A scar entry is about a moment that changed me. A lot of songs I was writing came from those scar entries.

We try to cover up scars. We stitch things up so it doesn’t leave a big mark. We slather ourselves in cream so we don’t age. I think it’s important to understand that we’re all going through life, and that’s what makes it a unique experience. Ugliness can be so beautiful, looking taboo, being unconventional — It’ll discriminate against you in some places, but you’ll find new people.

artist talk

yeule

speaks with

Hannah Rose Prendergast

first published

Issue No. 35, 02/2023

Which softscars track was the most challenging to make?

Technically, dazies. The time signature on that. Kin Leonn, my exec producer, and I recorded a bit of that at Abbey Road. There were so many revisions to it because I wanted to change the way I was singing. I wanted to sound closer to the live version, something in the low, low register. There’s an unreleased track, Are You Real?, that I couldn’t finish because every time I listened to it, I’d get triggered and start crying. It was too upsetting.

Feeling detached from reality can sometimes be dangerous; on the other hand, there’s a level of escapism that is healthy and necessary to the creative process — your music touches on that duality. How can you tell when an escape stops being safe?

When I started high school, I was hikikomori (socially removed from society.) I didn’t even leave my room. That really hurt me, but it made me feel so safe and detached from reality. The internet was a form of escape for me, but how I used it was wrong. I was creating this fake world by myself. It was inspiring, but I was in my head to the point where I was imagining things beyond comprehension. I’m a whole different person online, like a whole different persona. It’s not about being inauthentic but showing a part of myself that I repress. I see this anger and dark side to me sometimes when playing games.

Dissociation was a huge hobby of mine in 2021. It got so bad that I’d dissociate while doing something important, and it would get dangerous. My body was shutting down because everything was too overwhelming. I didn’t have the tools to handle strong emotions. I recommend CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy) or DBT (dialectical behavior therapy) to anyone with BPD (borderline personality disorder) or OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) — two things I struggle with.

Knowing that you’re tapping out is a scary thing. At this point in my life, I was just waking up and doing the motions. It took me so long to learn how to feed myself properly. Eating has been such a huge topic of conversation in my music. It’s still so silenced. The Barbie film didn’t even talk about it.

It’s a very dissociative act, the rituals we have when we’re in our heads. Sometimes on stage, I’m even dissociating, and I feel like most of my fans are also dissociating. It’s like one big dissociation party. This is a safe space, dissociate all you want, bestie.

Last Spring, you unveiled (n)secure at London’s Southbank Centre. Do you have any plans for your next installation? What would you like to create?

I’m exploring more set design and incorporating installations into my live shows. I want to do more galleries, but I'm a performer at the end of the day. I like to showcase that when I’m performing. I used to do a lot of sonic installations. I played around with code and built this room in the studio. (n)secure was the full-fleshed version of it.

team credits

seen Catharina Pavitschitz

styled Marianthi Hatzikidi

talent yeule

hair Man Wigs

assistants

photo Svetlana Igorievna

style Heeya Shewani

dress Seli Corsi

Can you expand on your belief that “part of the Asian struggle is having to be sublimated into whiteness to be seen as beautiful”?

I was doing a lot of essays on techno orientalism in uni because I was exploring the cyberpunk aesthetic in Hollywood films vs. Asian-made cyberpunk. The best way to describe [techno orientalism] is taking Asianess and making it part of this aesthetic. There’s a lot of sexualization.

It’s tokenism; you’re made to be decoration. The way Asians are portrayed in the media isn’t always out of understanding the culture or where you come from. It’s always about being bright, shiny, beautiful, and young. I love the idea of romanticizing and aestheticizing correctly. It’s the way you portray it, execute it, and respect you give it.

I was really into that conversation, especially living in the UK. I’ll never understand a black person’s perspective or struggle because it’s unique. The only thing we can do is help liberate that. Stop being so ignorant. No one will be able to understand the Asian struggle either, especially the feminine Asian struggle. So often, standards are assigned, and my role right now is to take, dissect, and subvert them.

Singapore is a multicultural country, so I grew up around many different types of people. There’s still light-skinned privilege extending to education and work opportunities. As someone who’s lived in a privileged position [in Singapore], moving to a white country was a completely different experience. I’m now the one having to deal with this. At the same time, I have to understand my privilege and other people’s struggle.

I feel like it’s also in a mindset. The visual world is so deeply engrained into what society is turning at, and what we consume is really important too. I love to reclaim things. I did Shibari (Japanese rope bondage) because I wanted to see myself and how I felt in that position. It was non-sexual, all for the art. There’s a difference between being sexy and being sexualized. Being sexy for yourself is very freeing. If you feel sexy, you look good, you feel confident, and you’re exuding that energy. Pursuing it because someone told you to do it is different. I love being sexy. It can also be sexy dressing like Wee Willie Winky. I still love myself in my black dysphoria hoodie.

You regularly practice showing kindness to AI by personifying your technological devices, keeping them functioning optimally. Do you think you’ll be in a good position when AI takes over?

I named my car Edward. I feel like he drives better when I’m really nice. It’s all about channeling the energy. My relationship with my devices is important because when you treat things well, they treat you well back. When I’m making music, trying to find a nice sound, I go by the feeling of how the knobs work. That’s why I love hardware. I don’t know if AI will take over, but I do know that it’s starting to replace people’s jobs.

In May this year, Grimes launched Elf Tech, designed to create AI versions of her vocals. What are your thoughts on this new venture? Is it something you would like to explore?

I love how innovative C (Claire) is. I think she’s so intelligent. I think people give her shit just because she’s female. I think it’s great. I’m interested in diving into something like that, but right now, I’m focusing on making more visual tech than AI tech. Visual tech is also very cool. I’m trying to see if there’s a tool to do the boring work. No one wants to mask shit.

As someone whose persona is so intricately tied with death and rebirth, what’s your stance on posthumous music release?

The proceeds [should] go to their family. I have no say on whether it’s ethical for a label to profit, but I feel it’s also remembering the person. I’m grateful to be surrounded by people who love me. I know they’ll represent me the way I want to be seen. I don’t think it’s controversial to release posthumously — remembering great art is very important. It depends on what’s going on behind the scenes, too.

What would it sound like if you could collaborate with the late Lou Reed?

I love him. I cried so hard when he died. I don’t know what it would sound like. We could use AI. Maybe I’ll just do it for myself for fun. There are a lot of loopholes we’d need to jump into with the label stuff. There should be a rule about that. You can only use the vocals of an artist who’s died. There would be an automated label and publisher contract based on how much content is used, and royalties are split according to the calculation. Lawyers will go out of business.

What do you look forward to sharing with your audience on the softscars tour this fall?

Touring always brings the reality that there are real yeule-enjoyers out there. I meet the sweetest fans ever who are so loving and kind and together taking care of each other. I get sweet gifts when I’m on tour. softscars will definitely be a crying fest for many. The screaming, sobbing lyrics I heard last year changed me. Touring is always very tiring, but I do love the experience. Sometimes the songs are perfectly played but not emotional. I want to be able to perform with a balance of that. This tour will be better because I have a band, so I’ll be surrounded by people I love and appreciate, people I’m close to. It’ll be a very new era for me, a different way of performing. I’ve always been alone on stage.

What scares you the most?

What scares me the most right now is running out of battery and having no food at home. I don’t want to be empty. I have to feed the sleep paralysis demons.

credit all images

(c) LE MILE & Catharina Pavitschitz

NOT A ROCK-DOC: The Sharks' Raw Rock Renaissance Film

NOT A ROCK-DOC: The Sharks' Raw Rock Renaissance Film

Unearthing a Rock Renaissance in Raw Intimacy

* NOT A ROCK-DOC

written Alban E. Smajli

LE MILE Magazine has been granted an exclusive glance into NOT A ROCK-DOC. Amidst a saturated market of rock documentaries, this particular one takes the lead, promising to stand distinct and apart from the rest.

The film exudes a refined irony, setting itself apart with an independent touch more akin to an art-house creation than a mainstream blockbuster. What about raw footage, the kind often dismissed in most films? Here, they're celebrated, acknowledged, and elevated.

Stephen W. „Steve“ Parsons & Anke Trojan

NOT A ROCK-DOC - A Sharks Tail, Film Directors

Enter Steve Parsons and Chris Spedding, the dynamic rock duo steering this narrative. Parsons harks back to a time when rock wasn't solely about the music, but also the attitude, the persona, and those introspective moments. Conversely, Spedding serves as the anchor, grounding the story with his unwavering passion and love for the genre.

Despite an obvious budgetary constraint, the film's ambition never wavers. Seamlessly integrating locales such as Berlin, Tokyo, and London, these cities become more than just scenic backdrops—they're woven into the very fabric of the narrative.

At the helm of this ambitious project are Steve Parsons and Anke Trojan. Parsons' roles in the film are a testament to his versatility, akin to a multitasking entrepreneur, deftly juggling multiple responsibilities. Their narrative salutes Sharks, the band overshadowed by unfortunate marketing missteps in the '70s.

A standout feature remains the undying commitment of fan Toshio to Chris Spedding. With each upload, Toshio isn’t merely chronicling performances; he's preserving a treasured era of rock, likely striking a chord with a passionate segment of aficionados.

Steve Parsons

seen by Aiste Saulyte

Toshio Nomura & Chris Spedding

NOT A ROCK DOC

The legacy of Sharks and the resonance of rock come alive and kick into today’s beat. For those keen to delve deeper and connect with this riveting narrative,

mark your calendars. The film is set to premiere on October 28 during the renowned Doc'n Roll Festival in London. But that's not all. Amplifying the experience will be a live Q&A session with Steve Parsons and Chris Spedding.

This is your chance to engage with the legends, delve into their memories, and understand the layers behind "NOT A ROCK-DOC". In an era that often looks ahead, here's an invitation to pause, reflect, and revel in a time that continues to echo in the corridors of rock history. Join the celebration, feel the beat, and be part of the rock renaissance.

Chris Spedding, Steve Parsons & Jordan Mooney

NOT A ROCK DOC

"Ride the sonic waves of 'NOT A ROCK-DOC' – a raw, unfiltered lens into rock's renaissance. Eager to vibe with Steve Parsons and Chris Spedding in a live Q&A? Score your tickets and immerse in the cult scene at the Doc'n Roll premiere:

Valentino x Triennale Milano 2023

Valentino x Triennale Milano 2023

Valentino & The Vanguard of Art

* A Harmonious Interlude at Triennale Milano

written Alban E. Smajli

As autumn blankets Milan, the city's fervor for fashion and art finds its epicenter at Triennale Milano, an institution that's been fostering a harmonious communion between diverse disciplines since its inception.

With the onset of their centenary celebrations, Triennale Milano raises the curtain to showcase "Italian Painting Today", a saga of contemporary Italian painting from the revolutionary 1960s to the transformative 2000s.

Maison Valentino's creative visionary, Pierpaolo Piccioli, often finds himself at intersections where art meanders into his world of fashion. He admits, "Every time my attention guides me towards an image, I always end up taking it with me, keeping it in a kind of archive of the mind where something happens – a connection, a color, a face." For him, this symbiotic relationship isn't necessarily about merging the domains of art and fashion but about letting them converse in spaces they have in common. The perfect embodiment of this philosophy was the Valentino Des Ateliers collection, conceived in the sanctity of the Atelier, where art and couture thrived in dialogue.

Piccioli's profound reflection on Hieronymus Bosch's triptych, "The Garden of Earthly Delights," during his first collection as Valentino's Creative Director, underscores the depth of his engagement with art. This piece, which incessantly occupied his mind, acted as a beacon, guiding him through uncertainties and pushing him to explore his own creative expanse.

049 Det VALENTINO, HC, Des Atelier

Benni Bosetto

Drawing on paper, 2020

Dating back to 1933, Triennale Milano has had a cherished relationship with painting, fostering dynamic dialogues between varying disciplines. "Italian Painting Today", curated by Damiano Gullì and exquisitely designed by Studio Italo Rota, continues this legacy, assembling 120 masterpieces from Italy's finest artists. Stefano Boeri, President of Triennale Milano, emphasizes the significance of this exhibit in celebrating Triennale's history while interpreting the contemporary art scene through the lens of painting.

These works, spanning from 2020 to 2023, reflect upon the myriad changes and challenges the world faced during these years, from the sweeping pandemic to the burgeoning influence of artificial intelligence on the fabric of artistry. Guglielmo Castelli and Francis Offman are among the illustrious names whose pieces, echoing themes of transformation and interpretation, grace the exhibition.

Maison Valentino's partnership with Triennale Milano, particularly for this exhibition, manifests Pierpaolo Piccioli's sentiment: "Maison Valentino is today a community that generates community, that seeks out spaces and means for creativity." Through the lens of "Italian Painting Today", the world beholds 120 keys, dreams, and pathways that unleash human complexity in liberating trajectories. This endeavor resonates with Piccioli's belief that the true essence of creation and hope emerges not from shared characteristics but from those that set us apart.

With the environment in focus, the exhibition design ensures minimal carbon footprint, incorporating materials that significantly reduce original material quantities and sidestepping the use of adhesives, paints, and welds.

Guglielmo Castelli

About today, 2019

mix technique on canvas

90 x 80 cm

021 Det VALENTINO, HC, Des Ateliers

Andrea Respino

bg QZ Respino, 2023

016 Det VALENTINO, HC, Des Ateliers

Sofia Silva

Festival Gondola, 2017

collage e olio su tela

collage and oil on canvas

43 x 53 cm

ph.C.Favero 190123_06_01

To further enrich this artistic voyage, Triennale Milano supplements the exhibition with a comprehensive catalogue, featuring introspections from key personalities like Stefano Boeri and Pierpaolo Piccioli, and a thought-provoking podcast penned by Tiziano Scarpa.

From October 25, 2023, to February 11, 2024, allow yourself to traverse the corridors of Triennale Milano, where art and fashion dance, not just in tandem but in pure, unadulterated symphony.

credits

(c) Valentino and all credited Artists

more to explore

www.triennale.org

Jerry McLaughlin - Demystifying Abstraction

Jerry McLaughlin - Demystifying Abstraction

Jerry McLaughlin

Demystifying Abstraction

written Savannah Winans

In an era where art is often made to be consumed on screens, flat and eye-catching, painter Jerry McLaughlin is dedicated to subtlety. McLaughlin’s highly textural surfaces and restrained palettes invite viewers to slow down and have a different type of perceptual experience with his work. Deceptively simple artworks leave room for nuanced reactions, especially when one ponders the significance of this type of art in a culture of excess.

Pure abstraction, or art that does not depict identifiable objects or figures, is often considered “difficult” art; it’s much harder for viewers to identify with shapes and colors rather than recognizable imagery. Of course, this difficulty of looking can produce unique and complex visual experiences, as it requires viewers to focus on gesture and material.

In this exclusive interview with LE MILE, Jerry McLaughlin gives insight into his process, inspirations, and the hard-to-define world of pure abstraction.

Jerry McLaughlin

structure no. 43, 2023

30x22 in

bog peat and willow ash on paper

.artist talk

Jerry McLaughlin

speaks with

Savannah Winans

Savannah Winans:

You studied medicine at the University of Cincinnati before transitioning into painting. How does your medical background inform your artmaking practice?

Jerry McLaughlin:

The most obvious answer is the emotional intensity of medicine. I was a pediatric critical care physician, which means I cared for children with life-threatening illnesses. Even though most children recover and go home, there is an enormous amount of trauma the child and family (and the medical team) experience. As a survival mechanism, I learned to disconnect from my feelings. That disconnect started to creep into my non-medicine life in ways I didn’t realize. I was really “shut down.” If I’m honest, I suppose I was quite “shut down” even as a boy. Medicine offered me more reason and opportunity to perfect that skill.

It sounds trite, but painting allowed me to visit those dark, disconnected places that I had been hiding from. Something about being alone in the studio, working intensely on paintings, in a space with no rules or demands—I could feel myself breathe and open up. I could feel all that sadness and hurt and anger, but not in this dramatic way you might imagine. When I paint, or think about painting, it’s like opening a small valve and this slow, steady stream comes out, letting the tank gradually empty. Only I know it will never empty; I just know it will never get that full again. And that’s enough.

There was a physical aspect to the type of medicine I practiced. I had to do technical procedures on my patients, and that required a lot of manual skill. I loved developing those skills. Painting requires manual skill, and I love that about it. Getting my tools and materials to do what I want is really important to me. I like doing things with my hands and doing things that challenge my dexterity. Finally, medicine and art both require a long-term commitment, both the learning and the doing. You never reach an endpoint. There is always more to learn and more to do. I like that kind of commitment. It’s a relationship.

Have you always worked in pure abstraction, or have you dabbled in representation? What led you to abstraction?

I’ve essentially always worked in pure abstraction. I was never the kind of kid (or adult) that sat around and drew things. When I was 10, the painting that made me want to become a painter was a Jackson Pollock action painting. It’s always been about abstraction for me. I did teach myself to draw and actually developed decent skills, but I never enjoyed it. I don’t enjoy recreating or representing what I see in front of me. I’m interested in ideas and feelings and words. I love abstract and conceptual thought. I must admit, a bit ashamedly, that I don’t even enjoy looking at representational work very much, certainly not depictive work. I appreciate it for what it is, but I really want the work to be abstracted or distorted in some way. I’ve always been drawn to art from the late 19th Century and forward, the “after Monet” period. So, working in pure abstraction was never a choice for me. It was the only path.

Jerry McLaughlin

soneto (xx), 2022

46x40in

oil cold wax wood ash on panel

Jerry McLaughlin

structure no. 47, 2023

30x22 in

bog peat and willow ash on paper

You’re considered an expert in cold wax medium, and co-authored a book on the topic. When did you discover cold wax, and how did it affect your work?

I initially painted with encaustic medium, which is “hot wax” that needs to be melted to be worked with. It requires use of a heat gun or a blow torch to move and fuse the layers. After several years of using encaustics, I was frustrated and a bit bored because I felt limited by the medium.

In the hopes of finding something that felt freer to me, I ordered some cold wax medium. At the time, there were no books or videos about it, so I really didn’t know what I was ordering. I didn’t even realize it was an oil painting medium, that I would need oil paints or some other kind of pigment to work with it. I just knew I wanted something different and was hoping to continue to work with beeswax, because I love it so much.

The first time I worked with cold wax, I fell in love with it. The texture, the organic quality of it. It was like an extension of my hands. It was what I had always imagined painting would be like. So, just a few days after receiving the cold wax, I abandoned encaustics altogether. I put away all my encaustic materials and never worked with them again.

Using cold wax transformed my work. It allowed me to layer and work with paint, pigments, and particulates in ways that encaustic never could. It freed me to develop textures and shapes and edges that felt expressive and natural to me. It was totally liberating. It helped me see a larger potential for my work and gave me a sense of possibility I never felt with encaustics.

You also incorporate ash into your paintings. How do you obtain the ash? In terms of the conceptual significance of the material, how does using ash change the painting, particularly in comparison to a material like cold wax?

I get the ash in my work from various sources. Most of it comes from my own fireplace or outdoor fire pit. I burn wood and plant debris from our property. I also burn my art pieces that simply do not work or that have lived their expressive life. I also collect ash from deliberately chosen sources. When I was in an artist residency in Ireland, I collected peat ash from the hearths of local homes where I stayed or visited. I have also collected ash from forest fires, from trash barrels in Mexican communities where there is no trash collection and so their only option is to burn their waste. I’m always looking for new and interesting sources.

Each pile of ash holds and tells the story of what came before it, and every fire produces its own unique ash. Even burning the same material gives different ash each time depending on the temperature of the fire, the amount of oxygen available, the duration of the fire, etc. Ash is not a single material. It is many.

Ash also has a range of textures, from chunky and woody to coarse and sandy to light and fluffy. Mixing ash with various media, including wax, adds its own unique texture to the medium. It also changes the body and viscosity of the medium, allowing me to manipulate it texturally. Each type of ash has its own coloration as well. Most are light to medium gray, but some are very black, and others have a brown or even ochre hue.

Using ash in my work brings a powerful aesthetic that is not possible with more traditional art media and carries with it universal symbolic elements: death, destruction, genesis, transformation, renewal, letting go, and so many more.

Your work is highly textural, so it can only be fully perceived in person. Do you see this as a deliberate reaction to the flattening effect of screens?

I have never thought about the texture in my work in those terms, so I have to say “no,” it’s not a reaction to that flatness. But my work does use texture in a very deliberate way that is connected to the flatness of screens.

All paintings are composed of five elements: color, shape, line, value, and texture. The first four are visual. We need our eyes to perceive them. Texture, however, is different. Although we can see texture, it is the only one we can also perceive with every square inch of our body. We can touch it. In fact, for physical texture, we don’t need our eyes at all. That physical aspect of a painting is something very powerful. Think about touching a tree when you’re walking in the woods, caressing an infant’s cheek, rubbing your dog’s belly, holding your friend’s hand, laying your cheek on your partner’s chest. There is an intimacy there that goes beyond visual. Physical texture evokes emotion in ways that the other visual elements cannot. And that is why I use texture the way I do, to elicit emotion and to create intimacy with my viewers.

While the texture in my work is not a deliberate reaction to the flatness of digital screens, it is a deliberate use of an element that cannot be captured by screens, an element that must be experienced in person to appreciate.

You look to poetry for artistic inspiration, which I find very interesting as poetry is a sort of abstraction of language. How does poetry guide your painting process? Are there any specific quotes or poems that seem particularly important to your recent body of work?

Poetry is a type of abstraction of language. So much of poetry is about moods and capturing a feeling. It’s about using words to capture something that transcends words. But poetry can also be just as much about formality, about a structure around stanza, syllable, rhyme, and meter.

For me, abstract painting is the same. It’s an attempt to evoke a mood or capture a feeling, capture something that transcends the physicality of a painting. In my own work, there is a formality. I set rules around media, shape, texture, color, line, and shape. I have to follow those rules yet still create something evocative and beautiful.

I suppose in many ways I’m using poetry to navigate the mess of feelings that live inside of me. It helps me find and focus my emotions; helps me clarify and distill what I want to say. I usually read before I start painting. Sometimes it's pages of poems, sometimes just a few lines. But when I’m done, I have a clarity that lets me be more focused and deliberate in my painting.

You moved to central Mexico a few years ago, and your series “adobe y negro” is inspired by the architecture and light of your new surroundings. Although your paintings are devoid of representational elements, this series is about a specific place. Can you speak on the connection between abstraction and place?

I’m not an artist who paints about place. My work is much more about the junction of formal ideas, moods, and feelings. But abstraction requires a visual vocabulary, and that vocabulary must come from somewhere. It's quite natural for an artist’s environment to impact their visual vocabulary. We tend to absorb the language around us, and that language comes in many forms: the local foods, the local styles, the local slang, even sometimes the local attitudes. Why wouldn’t an artist absorb the colors, shapes, lines, and textures around them? However, we often choose our environments because they appeal to us, and the potential visual vocabulary of any environment is enormous. So, I think that we absorb the visual vocabulary that feels personal to us based on our own aesthetics and personal tendencies.

People often say to me, “Oh, you live in San Miguel. It’s so beautiful there. It must really come out in your work.” Well, it definitely does, but not in the way they usually mean. They are talking about the bright reds and yellows and oranges of the walls, the flowers, the birds and trees. But that is not what comes into my work. Instead, it’s the grays and browns and whites of concrete and steel, of adobe and plaster, the geometry and edges of modern Mexican architecture. I’m sure there are artists whose vocabulary is not influenced by their environment, but I think for most of us we choose our environment because it speaks to us, and we absorb from that environment the vocabulary that speaks to us.

Your palette is quite restrained, consisting mostly of white, gray, brown, and black. What draws you to these colors?

This is a bit like asking someone why their favorite color is blue. Why are any of us drawn to specific colors? But I am glad you refer to them as colors. People have often asked me, “Why don’t you work with color?” as if black and white and gray aren’t colors, and only blues, greens, purples, etc. qualify as colors.

I guess a large part of my answer is simply that I’m drawn to them. I like them aesthetically. Something about those neutrals feels right to me. And the range of them is vast. It’s amazing how many blacks, whites, grays, and browns there are to work with and discover. They can be challenging colors to work with effectively as well. I like that challenge.

There is also something universal about those colors. They are the colors of natural materials: sand, soil, stone, clay, ash, and char. But they are also the colors of industrial and structural materials: concrete, cinderblock, steel, iron, adobe, and plaster. They are the colors of shadows. I love shadows, and I love all those materials.

These colors carry a mood of the natural and the industrial. Their mood also feels restrained to me, subtle. Restraint and subtlety are important to me. They also carry the moods I want to bring to my work: melancholy, longing, loss, hurt—moods people might consider dark or difficult.

Can you list some of your favorite abstract artists and describe the effect they had on you?

There are so many, but here are a few that come to mind as being particularly influential.

Pierre Soulages. I had started my “oscuro” series and was really enjoying the exploration of black through shape and texture when someone said to me, “You must love the work of Pierre Soulages.” I was so embarrassed, because I’d never heard of him. Of course, I looked him up immediately and loved the work. I ordered some books. And within a few weeks I had arranged a trip to France solely to see his work at the Pompidou, an exhibition of his work at the Louvre, and a trip to his museum in Rodez. I was in Rodez for three days and went to the museum every day. It was a powerful experience for me. It’s not just his use of black in his “outrenoirs” but his overall use of shape and texture and his near obsession with darkness in his work. It changed the way I look at painting. Seeing someone devote their career to darkness was liberating. And, of course, the sheer beauty of the work is inspiring. The richness and lusciousness of his surfaces, the importance of the paint or ink itself as an important subject of the work.

Nicolas de Staël. His heavy application of paint and the building of layers to arrive at actual physical, dimensional shapes on the surface of the work. His rough-edged geometry and the structure of his compositions. I’m particularly drawn to his works with a neutral palette. The subtlety of his coloration through heavy texture and layering is incredible. His paintings make me want to continue to explore the physical, textural aspects of my own work, to continue to explore how I handle edges, how I structure and compose the shapes in my work. The moods in his darker works, those somber moods that come from that neutral palette, that texture and geometry, they bring me to the kind of place I feel when I’m making my own work. I’m actually going to France this winter specifically to see a retrospective of his work at the Modern Art Museum in Paris. I’m excited to have the opportunity to be physically in front of so much of his work, to experience the physicality of it.

Hideake Yamanobe. I came across his work online years ago and was captivated by the combination of minimalism, materiality, and expressivity in the work. They tend to be smaller works. Historically I thought that for most minimalist work to “work” there was an aspect of larger scale required. His work taught me that isn’t true at all. It just has to be done correctly. He’s having an exhibition right now in Cologne, Germany. I wish I could go. I’ve never seen his work in person.

What feelings do your paintings evoke in your viewers, and how do those feelings differ from your own?

When I think about my own work, there are aspects I know I want to be there. I want the work to be visually beautiful. I also want the work to be emotionally beautiful but dark, like a memory of someone we’ve lost, like melancholy or longing. I want my work to feel powerful but in a restrained way. I want it to feel technically well executed, sophisticated, and nuanced in its composition, palette, and textures. I feel all of that in my work, but to convey that requires a specific connection and intimacy with the viewer.

I want people to be drawn to my work both physically and emotionally. I think for those people who do connect with my work, they connect with what I’m trying to achieve. I think it’s tough to not see the darkness, the formalism. Hopefully they think it’s beautiful, too. I doubt anyone walks away from my work feeling happy, energetic, or playful. I hope they do walk away appreciating the technical and formal aspects of the painting and they walk away feeling quiet and feeling touched somehow.

What are you currently working on?

I’m very excited right now. I have two projects going on.

The first is a continuation of the project I started at my artist residency in Ireland, painting with ash, using it as the only pigment and textural material. There is no actual paint. All the coloration comes from the ash itself. Any linework is drawn using charcoal I collect from the ash fires or make from recycled artwork. I use cold wax and acrylic medium as the binders. I’m in love with figuring out all the ways I can make the material do new and different things. Most of the work is on paper, and I build the pieces in only a few layers, sometimes just two or three. The work is very spontaneous and gesturally expressive. My movements, bold and subtle, are immediately recorded. But the line work is more strict. It brings structural and formal contrast to the gestural shapes. I’m exploring various types of ash and various ways of processing the ash to get different colors and textural characteristics from it. I’m also experimenting with canvas and wood panels as substrates.

The second project is an extension of my “oscuro” series: all black paintings that are an exploration of texture, shape, and surface. I’m expanding this series to push more deeply into the meaning of the word “oscuro” (or “darkness,” in English). I’m expanding the exploration of scale to include much larger and smaller works. Additionally, I’m pushing beyond just paint to explore darkness, including other materials such as concrete, paper, steel, sand, ash, textiles, and more. There is also 3D work. This series is much more conceptual, and I envision an entire body of work that could span multiple exhibitions.

credits

(c) Jerry McLaughlin

Ivan McClellan photographs Cowboys of Color

Ivan McClellan photographs Cowboys of Color

Ivan McClellan

Reclaiming Western Mythology by Cultivating Bonds

written Mariepet Mangosing

Brought up in Kansas City, natural storyteller and photographer Ivan McClellan always thought of himself as strictly a city kid.

His understanding of the place he grew up in was one that hadn’t been fully realized, as it seemingly existed diametrically opposed to the rural country town and culture that was characterized around him.

McClellan notes, “my experience was very urban but very country at the same time. We would hang out in the 5-acre field behind our house and would pick blackberries, catch fireflies. Some real country stuff. We had neighbors who had cows and chickens. Then at the same time, there was gang violence and police were driving up and down the streets. There were 2,000 kids in my high school. It was this mix of city and country living all at once.” Questioning the full scope of these identities and traits is eventually what led to McClellan’s indelible interest in delving further into his self-understanding and the communities around him. The opportunity, as random and serendipitous as it was, revealed itself in an unexpected way: cowboys and the rodeo.

Ivan McClellan

Benjamin Scott

courtesy of the artist

.artist talk

Ivan McClellan

speaks with

Mariepet Mangosing

first published in

Issue Nr. 33, 02/2022

During his childhood, McClellan had attended the American Royal Rodeo with his school choir to sing the National Anthem at the event. While he had already been introduced to rodeo, McClellan had missed a major point of interest that would permanently shift his perspective as an artist and creative. Having established himself as a designer and photographer, he shares, "I never took interest in any of the country stuff that we were doing until 2015. I was already working and living in Portland, when I met filmmaker Charles Perry. He introduced me to his documentary about black cowboys. Later that summer, I went with him to Oklahoma to a rodeo.” Unsure what to expect, McClellan’s eyes were widened by the experience. He immediately felt comfort in the dichotomy of the people that flooded the gates, saying, “I met thousands of black cowboys. Young men with no shirts on and gold chains, riding their horses in basketball shorts. There were old men with perfect Stetsons and pinky rings. Women with braids and acrylic nails. Barrel racing. I kept going back.” Enthralled by what he saw, McClellan would take the excursion back to Oklahoma every year.

Upon one of his returns, McClellan found himself making friends with the cowboys and the attendees. He recalls his first encounter with one of them, someone who has become one of his friends, saying, “Robert Criff offered me a bottle of water. He had a Kansas City hat on and I asked, ‘Where are you from?’ Turned out he lived on the other side of the 5-acre field where my sister and I played. He knew my grandma and we went to the same high school. He explained to me that half of these people come to the rodeo for their big family reunions.” It was after this chance meeting with Criff that McClellan had an “aha moment.” McClellan was being called upon to reconnect with his roots in a way that he hadn’t thought of before. “This is my culture and my people,” he says. “It changed my perception of home away from this urban place of poverty to this place of cowboys and independence. It was an amazing, transformative moment for me. To put it simply and plainly: I was living in Portland. It was very white. So this was an opportunity to be around the culture. Something that was my own.”

Ivan McClellan

Tiffanie and Liam Carter

courtesy of the artist

Through revisiting his home and learning about the community on the other side of his backyard, McClellan opened himself up to all aspects of the rodeo. At first, McClellan struggled with certain practices of the sport, specifically calf roping. McClellan reflects on his own privilege, checking it at the door, as he realized that this is the reality for a lot of the people in the farming industry. He defers to experiencing it all without judgment. “My work is about the people. I had trouble with calf roping for how brutal and stressful to the animals it seemed. But I had to take a step back. You don’t know what you’re looking at. This is an entirely different culture. This is an expression of rural life that has gone on since slavery. These are practices that happen every day on a working farm. I need to let go of my judgment as a city boy and observe it for what it is.”

With open-mindedness, McClellan was able to see something more powerful and bigger than him. “You have people that are shelling out to give it a shot. Everyone is welcome and supported at the rodeo. They’re really family events. There’s a lot of love and support in the sport that you don’t really see elsewhere.”

Further exploring the inherent camaraderie of the sport, McClellan’s creative mission crystallized. He shares an anecdote about his first meeting with Sticky Haynes, the first of many subjects he would return to and cultivate a close bond with. “We met and Sticky said, ‘You can ride with me.’ He had a two-ton bull in the back of the truck, going nuts. We drove three hours to College Station. While on the road driving, he’s spitting dip in a McDonald’s cup. When we got back to his home, I took pictures inside of his trailer.”

McClellan would develop his project Eight Seconds through this intimate narrative lens. “Sticky told me that there’s a trailer on the property because he was still trying to raise money. His house got torn up by a hurricane. It was then that I thought these are the kind of stories that felt more compelling. It held more depth. As the project went on, I would be visiting the same folks over and over again.”

As McClellan was introduced to other members of this community, he realized a common thread amongst the cowboys and the ranchers: the idea of land and who might own it. “As I moved away from the rodeo events and started going to the places people lived, the land and the dirt they occupied, and ownership came into play. Many of these cowboys didn’t have their own property, boarded their horses, and leased land on a ranch. If you came upon black folks that owned land, it was inherited for years. From when their ancestors were freed as enslaved people, they paid taxes every year and kept their land.” The idea that people did not necessarily possess the land they lived on, but rather were visitors taking care of what had been graciously handed down to them.

Ivan McClellan

Pony Express Race

courtesy of the artist

In that way, McClellan contemplates what that might mean to the project and black history in sum. “I went to North Carolina and hung out with a man named Julius Tillery. He runs a company named Black Cotton. I was overwhelmed when he took me out into the cotton fields; something that brought up fear. Generations ago, my ancestors would have been out here with sore hands from picking cotton manually. Now, Tillery has a machine that picks the cotton to process. He then takes it down the street to a cotton gin, turning it into pure cotton cloth that you can sell. This machine was invented by Eli Whitney. If that machine had not been invented, slavery would have ended years prior. That machine made slavery boom when it was already in decline. Now, a black man owns a cotton gin and this land that his family has had for generations. It was a powerful moment, a transformative moment.”

McClellan ultimately hopes to reclaim the mythology and history around Western portraits. Eight Seconds affords McClellan the opportunity to learn more about himself, the culture that raised him, and the importance of highlighting black joy. McClellan succeeds in this mission, recounting his first solo show in Cody, Wyoming, the self-proclaimed Rodeo Capital of the World. “My work was displayed at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show created these fixated myths of the cowboy that you see on TV and films. There’s a whole floor about this man and the myth that he created. Forty of my photos of contemporary and real black cowboys and their stories sat right underneath this shrine of whiteness. Then it dawned on me. That the work was a disruption of that. It aimed to be a place where young white folks passing through to Yellowstone would encounter and ask questions about their beliefs and be challenged. While I prefer not to have my work under the white gaze, I made these photos to uplift black folks and that’s exciting to me. There are a lot of black folks who don’t know about this culture as well. I’m proud to be a steward of that message.”

Ivan McClellan

Hollywood Cowboys

courtesy of the artist

Eight Seconds represents friendship and community and what it takes to cultivate those bonds. McClellan is able to evade just “helicoptering in” and merely taking photos. He is forming something deeper and meaningful while redefining the idea of Western history and identity in this particular landscape by way of simply sharing what he sees and telling the stories he observes. While it has been seven years since he began this project and he feels like it might end, McClellan continues to learn something new every time. McClellan’s wife believes that despite the fact that he wants to throw his hat in, McClellan will be doing this until he is 70 years old. With every passing rodeo season, at the helm is a story worth being told, and McClellan rightfully wants to be there.

credits

(c) Ivan McClellan

Artist Talk - Interview with thr33som3s

Artist Talk - Interview with thr33som3s

.aesthetic talk

Guiding the Grotto

* Artist thr33som3s and his new generative art solo exhibition Dialogu3

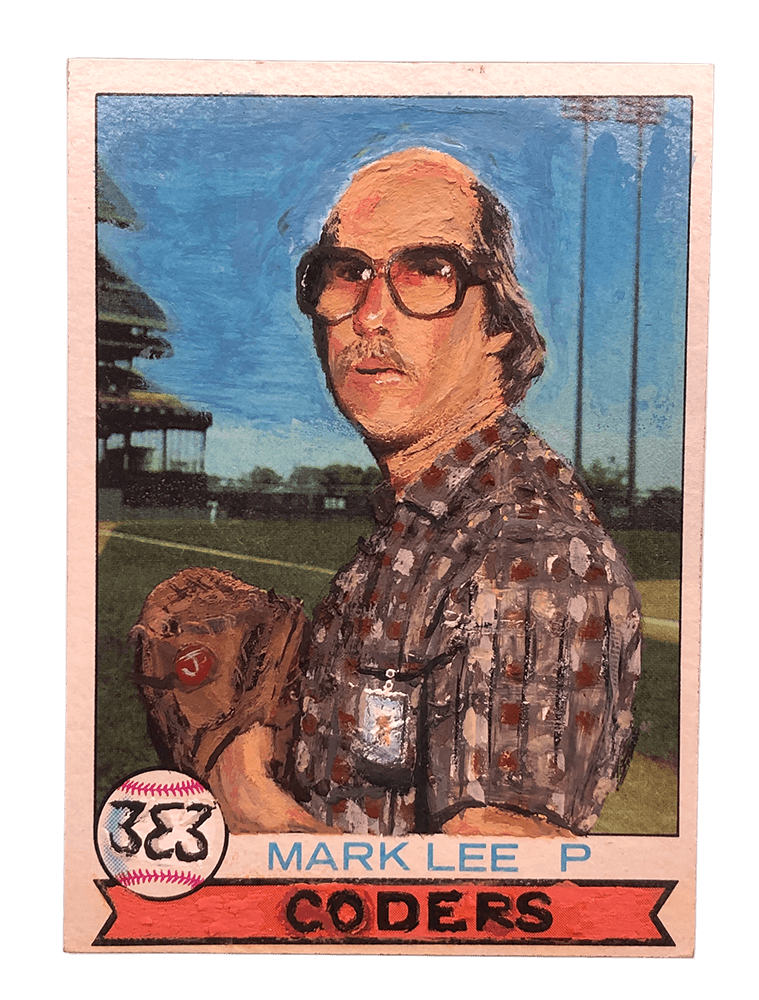

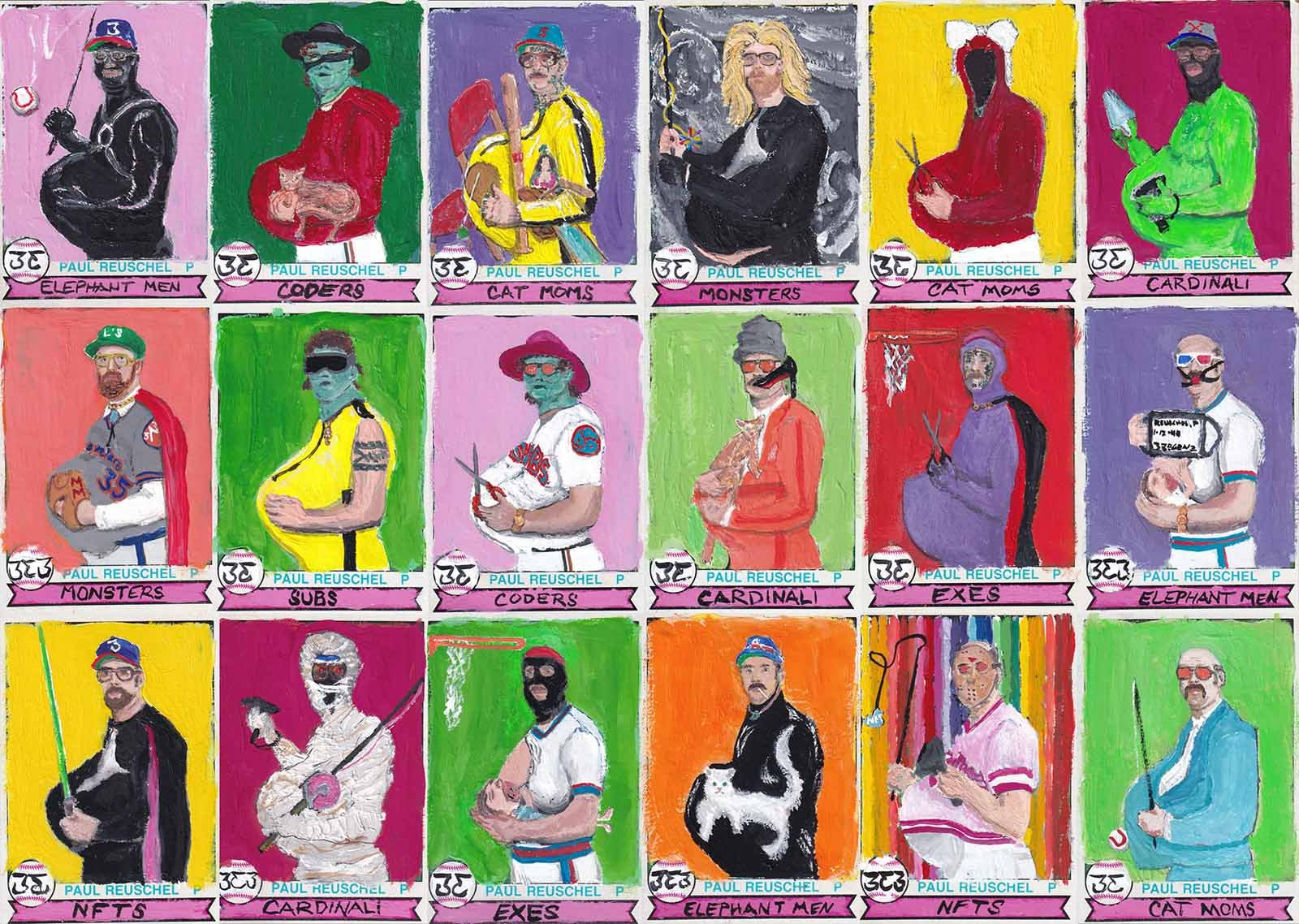

Enter a conceptual universe with a cult-following unlike any other: satirical, subversive, kaleidoscopic, and innovative in ways that are sometimes hard to comprehend. thr33som3s is both the enigmatic persona and living project of the pseudonymous artist whose gouache paintings on vintage baseball cards form the foundation his practice and the Grotto, a community of collectors who inhabit various roles in this fictionalized baseball league and enact evolving narratives dictated by the artist, uncontrollable events, and the blockchain.

„I think the use of old baseball cards provides something tangible and familiar to the viewer.”

With his solo exhibition, Dialogue3, at Vellum LA in Los Angeles, thr33som3s offers a rare glimpse into the inner workings of his notoriously labyrinthine world. Harkening back to the advent of generative art in the 1960s and 70s, when such art was still made by hand, thr33som3s’s generative practice, thr33zi3s, finds him physically altering existing paintings — often multiple times for a single work and over periods of time — as dictated by blockchain interactions with his collectors.

Through such interactions, thr33som3s encourages active participation in the creation and destruction of his work with seemingly no end in sight to the narrative possibilities and lucrative antics that can ensue.

LE MILE //

You started painting in your forties. What was your life like before then and what made you decide to start creating art?

thr33som3s //

Early in my life I put all my creative energies into baseball. When my baseball career ended, I took that focus and put it into creating businesses. By my forties, I found myself trapped in a mega-corporate structure that stifled that creativity, and I think that’s where I found painting as a necessary outlet.

Who are your artistic influences?

I think I’ve always drawn the most influence from cinema. Martin Scorsese, Sam Peckinpah, and Pedro Almodóvar for images; John Sayles and Ron Shelton for stories. I love the work of Christo and Jeanne Claude and draw great inspiration from their process, particularly their economization of their work in order to maintain absolute control of it all.

While you paint on vintage baseball cards, you often refrain from any “baseball” labels. What do you hope viewers can take away from the style of the paintings themselves?

I think the use of old baseball cards provides something tangible and familiar to the viewer. I hope my painting coaxes them to see beyond what they expect and know into, perhaps, a parallel dimension. Yes, it is just a baseball card, but the painted image forces the idea that it’s not. Something can be two things at once. It’s why I go back and forth between calling my work “paintings” and “cards.”

You purposefully misuse gouache when you paint?

Yes, it came early to my practice and it’s kind of the main medium I’m even familiar with, and I haven’t found anything else that lets me subtract as much as I add when I am changing a previously painted image.

If any of these characters could speak, what would they say?

Who’s to say they can’t speak?

When did your painting practice converge with the blockchain?

I first heard of blockchain in 2013, but I didn’t hear about collectibles or art on-chain until fall of 2020. By December of 2020, I was looking closely at options I might have to bring my paintings on-chain, and I minted my first piece on Tezos in June of 2021.

.artist talk

thr33som3s

In a previous interview you call your “analog generative” approach to producing work “the purest form of generative art on the blockchain.” What do you mean by that?

Let’s just say, I don’t call the results of my generative work “outputs.” Work created by human hands, whose very essence can’t exist without generative blockchain interaction, is pretty damn pure.

Because you constantly alter your paintings, do they have an inherent ephemeral quality that you think adds to the experience of your work?

I like to think I play a bit of a game with my collectors and my work as far as the ephemeral goes. As long as I possess the painting and can alter it based on the ongoing dialog with the collector, none of it is permanent. But, as soon as I release the physical painting to a collector, then it is out of my control. At that point I can say it is finished. It's what I do with thr33zi3s, the most interactive of all my works, by charging the collector with the responsibility of choosing to continually evolve the painting and hold and use the NFT or to give all that up to claim the physical and put an end to its evolution. I let the collector, in essence, determine when the painting is finished.

The Grotto is full of those merely observing on the “bleachers” to those who are fully entrenched in this conceptual universe, managing different teams, assuming different roles. What do you think motivates someone to tip the scale from curious spectator to die-hard believer?

The Grotto came for the money and they stayed for the culture.

You offer the Grotto a lot of freedom of choice when it comes to how work is collected, alters, and evolves over time. Has there been a moment when the Grotto surprised you or changed the way you think about your relationship to offering them, essentially, free will?

We are only a little over two years into the Grotto aspect of the project, and they're still getting their footing and understanding how very much they affect the volume and structure of my work. If anything, I think I've been surprised at how willing they are to dive into that aspect of the project and their courage to destroy work worth many hundreds of thousands of dollars in exercising that power to guide my creations.

In your upcoming exhibition, Dialogu3, at Vellum LA, what dialogues do you hope to convey to the uninitiated viewer? Are there any dialogues you wish to explore further?

On the surface, the title refers to the conversation between me and my collectors that takes place via the blockchain. But as this show and this particular work reaches new eyes, I want it to prompt an inner dialogue between the viewer and their very own concept of art. Has their conversation with a work ever gone beyond viewing it or owning it? Have they even considered an active participation in the work? How would they behave with a piece if a continuing dialogue with the artist were possible? In exploring these thoughts, I hope they can start to imagine what is possible with blockchain and start to demand it of their future collecting.

In Dialogue3, for the first time, you are exhibiting physical and blockchain-backed paintings together. What do you hope one communicates about the other?

I don't think most people get a true sense of the size and scale of my physical paintings as most of the time they are seen on screens. So, there's certainly something exciting about seeing the physicals at 2.5"x3.5" in rooms where they are being shown digitally, as large as 6' tall each. Beyond the size, I hope the viewer is drawn into the thr33zi3s paintings to see the particular traits the blockchain decided I would paint, then to look up as all of my work literally floats around the room. One would be able to search out the specific components of a given painting by finding its corresponding paintings in the rest of my work. I think it will be a fun treasure hunt of sorts. It also looks forward to all the possible combinations in future thr33zi3s generations that lay ahead as my oeuvre grows and expands.

credit all images

(c) the artists thr33som3s

.aesthetic talk - Exclusive with Mattia Carrano

.aesthetic talk - Exclusive with Mattia Carrano

Mattia Carrano Unplugged

Instinct, Fashion & Digital Disconnects

interview Michelle Heath

written Alban E. Smajli

In a world where polished facades often trump raw truths, LE MILE sits down with Italy's cinematic wildcard, Mattia Carrano.

Without the chains of traditional acting methods, Carrano reveals the uncharted territories of his instinctive approach. He's a rebel with a perspective, teetering between the intoxicating allure of fashion's ambition and the unadulterated emotional core of his performances.

But don’t mistake this for just another actor's tell-all. As conversations shift from face-to-face to pixel-to-pixel, Carrano is candid about our collective digital detox and how we’re losing the art of true connection. With the backdrop of Prisma and the evolving language of fashion, we dive deep into a world where dialogues are crafted, not dictated, and where authenticity, even in silence, speaks volumes.

tshirt Arthur Arbesser

trousers Yohji Yamamoto

jumper Hermes

ring Arlo Haisek

.artist talk

Mattia Carrano

speaks with

Michelle Heath

first published

Issue Nr. 34, 01/2023

total look Jil Sander by Lucie and Luke Meier

Michelle Heath

You said that since you have no professional training in acting, you work on instinct. Do you think this helps you to some extent in your work, as you are not burdened with formality and structure?

Mattia Carrano

I think so. Certainly, at the beginning, not knowing where I was and what I was doing didn't help me. But after just a couple of months of having a broad knowledge of my characters, not having set schemes aided me in expressing my true emotions.

Do you think working in fashion shoots is an extension of acting?

In my opinion, they are two separate sectors that can coexist, but they might never even meet.

Some designers create pieces that act like armor or reference a certain person. Do you like fashion that is as ambitious as this, or is it more complementary to you? How would you describe your personal style?

I've always loved to see fashion, but I've never been a big fanatic. I find that ambitious fashion sparks great curiosity in the eye of the beholder. At the moment, my style is very simple, but with time and greater fashion awareness, I'd like to experiment and become interested in different styles.

You mentioned that people are no longer accustomed to dialogue. Why do you think this is the case?

It's because, with so many ways to communicate, such as through social networks, it often becomes more challenging to have face-to-face dialogues.

Do you think shows like Prisma, which focus on topics like gender, are instrumental in helping bring people back to a world of dialogue and sharing?

Of course, anything that provides information will inevitably lead to dialogue, and that dialogue will foster sharing.

full look KENZO

foulard Arthur Arbesser

shirt Valentino

What role do you think fashion can play in this return to dialogue?

In my opinion, the way we present ourselves through fashion is also a form of dialogue.

So, do you prefer to call or write? Verbal dialogue can feel very different from communication via text or email. Is it more about the medium of the dialogue, or is the mere act of communicating what truly matters?

I prefer calling. When dialogue takes place, what's often missing is eye contact.

Your work at PRISMA is so meaningful and profound. What awaits you next?

I aim to continue evoking emotions.

credits

(c) Kristijan Vojinovic

Alfie Kungu - Freedom to play and explore

Alfie Kungu - Freedom to play and explore

Alfie Kungu

Freedom to play and explore

written Tagen Donovan

Alfie Kungu’s extraverted manner projects an aesthetic of maximalism. His work is visually impactful, embracing immersive scales with implementation of vivid colours palettes, textures, and whimsical forms. Approaching his canvas with an equal measure of refinement and a set of enviable instincts — Kungu evokes a sense of warmth and tenderness.